In 1985, Donald Denoon asked whether capitalism in Papua New Guinea (PNG) had produced development or underdevelopment. But he was less interested in choosing sides and more interested in showing why both answers are too simple. Slightly off from his question but insightfully, he concluded that PNG experienced a colonialism without capital and a capitalism without transformation. What does that mean?

Let’s go back to history. Before colonial rule, PNG’s tribal economies revolved around reciprocity. Wealth circulated through ceremonial exchange and obligations rather than through impersonal markets. These systems sustained our societies for millennia but failed to generate the cycles of reinvestment that could have made capitalism dynamic. During those times, signs of shifts towards capitalist modes of production from within were limited; the pressure to change then would come from outside.

In 1884, European annexation started and would have promised that transformation. But in practice it brought little real investment. Australia, which, then, assumed responsibility, saw PNG less as an economic frontier and more as a strategic shield. Plantations were few and often failed, gold discoveries were patchy, and infrastructures were barely developed. So, by the eve of World War II, colonialism was more administration and control with little infusion of capital. Denoon described this as “colonialism without capital”.

Post-war decades did create a new dynamic, but not one that led towards industrial capitalism. Australia significantly expanded its financial support, funding health, education, and administration. Though these services matter, according to Denoon, they did not generate new productive capacity. So, he calls this “goulash colonialism”: a state apparatus heavy on social services but light on productive assets. Private investment stayed away, except in small enclaves. The rural economy relied largely on smallholder coffee and copra producers, who did expand their output, but the bigger picture was that of dependency.

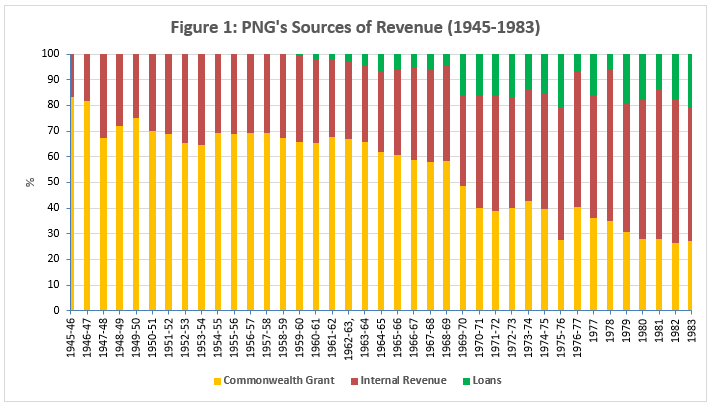

By 1960s, PNG looked less like an emerging capitalist economy than like Australia’s poorest state, merely surviving on grants and subsidies (Figure 1). But the grant given as a share of total grants to other states has never exceeded 10 per cent and was already on decline starting late 1950s and hit below 2 per cent when PNG got independence in 1975 (Figure 2).

When PNG got its independence, the dependency dilemma got fully exposed. Michael Somare’s government inherited a large, costly administration built on external funds. Self-reliance would have required dismantling much of what had been created, while maintaining services meant embracing long-term dependence on Australian aid and foreign mining companies. The government chose the second path, to preserve health, education, and roads. This bargain shaped the post-independence economy. It ties state finances to resource enclaves and donors.

Dependency theorists argued that PNG was underdeveloped given its enclave mining, weak manufacturing, and reliance on aid. However, critics such as Bruce Knapman also countered that there was evidence of development such as structural change, spread of money, and limited per capita gains. Denoon’s thinks differently. He described PNG as having a “truncated capitalism”. The institutions and legal framework were in place, and mining enclaves operated as capitalist ventures, but the deeper foundations, such as an industrial working class, widespread wage dependence, and reinvestment of capital, remain incomplete. Capitalism was only imminent. Not immanent.

According to Denoon, PNG’s economic trajectory was shaped by Australian strategic motives. Canberra’s priority was defence, not economic transformation. There was social conservatism at the village level and a willingness to subsidise services rather than a strong push for disruptive capitalist change. This creates a hybrid system of a large state, financed by grants, while rural smallholders sustain exports, mining enclaves dominate revenues, and vast areas of subsistence agriculture remain untouched by markets.

Forty years on since Denoon wrote the paper, PNG still grapples with a service-heavy state that still relies on aid, has an economy which is still heavily reliant on resource projects, and a massive subsistence sector that remains locked. One could say capitalism arrived in PNG in fragments, interacted with traditional systems, and produced something that was neither fully capitalist nor wholly traditional. For Denoon, this blurs the binary classification of development and underdevelopment.

So to answer his question of whether PNG is developed or underdeveloped, he looks instead to questions of what kind of capitalism was introduced, how it was sustained, and who it served. And his answer was that it was a half-built capitalism, reliant on outside aid and mining enclaves—still evident today.

Ref:

This blog is a review of Donald Denoon’s paper titled, Capitalism in Papua New Guinea: Development or Underdevelopment. Data for the graphs were taken from the same paper.

The cover photo of Tari Wigman is taken from International Travel News.

Leave a comment