Life expectancy is one of the key indicators of overall quality of life. This post uses World Bank’s estimates, to show three major trends of life expectancy in Melanesia.

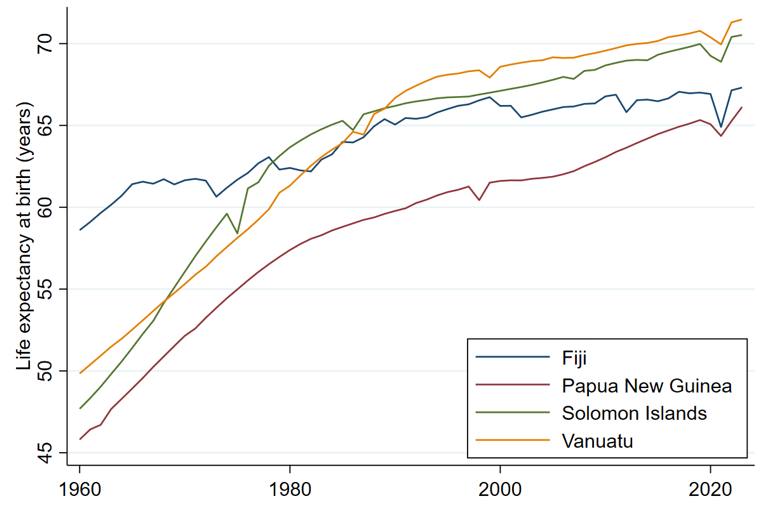

First is the catching up of other countries to Fiji (figure 1). In the 1960s, being born in Fiji would give you a decade’s advantage in life expectancy over your Melanesian neighbours. A Fijian child could expect to live well into their late fifties, while a child born in Papua New Guinea (PNG) might not see their late forties.

However, Fiji’s gains plateaued by the 1990s, and others caught up. The Solomon Islands and Vanuatu experienced rapid improvements from the late 1970s onward. By the 2020s, all four countries had converged around the mid-60s level. Today, a newborn in Port Vila or Honiara can expect to live almost as long as one in Suva. That’s an extraordinary equalisation across vastly different geographies and economies.

In PNG, progress has been slow but steady, with life expectancy rising by roughly 15 years since independence in 1975. Comparatively, this country has remained a laggard since the 1960s. Not because it has failed to improve, but the rest have improved faster. So, if you want to live a short life in Melanesia? Be a Papua New Guinean! Haha.

Figure 1: Melanesians Life Expectancies (1960-2023)

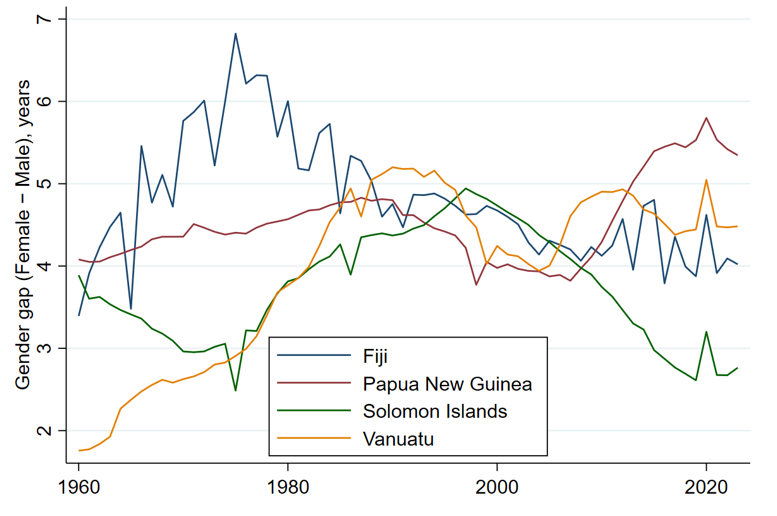

Jokes aside. Despite these gains of longer life expectancies since the 1960s, there is another story when we split the data by gender (Figure 2). That’s our second trend. Women consistently outlive men in every country by about three to seven years, and broadly, that gap hasn’t changed much since the 1960s. In 2023, the average gap across the region is 4 years, consistent with the global average.

Figure 2: Life Expectancies by Gender (1960-2023)

While women undeniably lived longer than men, Figure 3 below shows even more interesting patterns. On the less encouraging side, PNG—after maintaining a relatively stable life expectancy gap between the 1960s and 2010—has seen that gap widen in recent years, now the largest among its Melanesian peers. This could suggest that either the quality of life for men in PNG has deteriorated or that women’s health and longevity have improved at a faster pace than men’s.

But if we compared the gaps to their initial conditions, Vanuatu is the country with the most widening gap, twice the size to that of when they started in the 1960s. In Fiji, the gap peaked in the 1970s at nearly seven years, but, until the 1990s, it joined Vanuatu, and both fluctuated within the band of four to five years. For these three countries, PNG, Fiji and Vanuatu, closing the gender divide looks unlikely anytime soon. This is inconsistent with the declining life expectancy gap between men and women that has been observed in other parts of the world.

On the promising side of the story, one that is riding with the global trend, is the Solomon Islands. Since the late 1990s, its life expectancy’s gender gap has been steadily shrinking, hitting below three years in 2023.

Figure 3: Gender Gap in Life Expectancies (1960-2023)

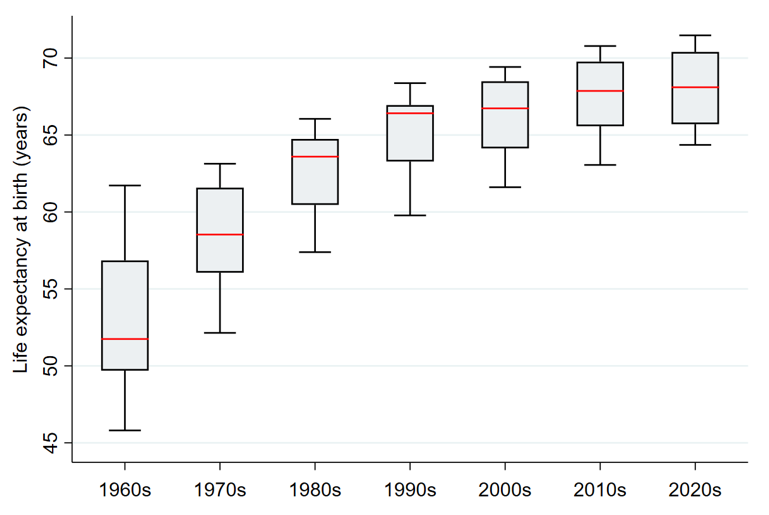

Figure 4 illustrates the third and final trend. Each decade’s boxplot shows not just higher medians but shrinking spreads. Broadly, life expectancy across Melanesia has become both longer and more equal. The lowest performers have caught up with the highest. The region has moved from health divergence to health convergence, and quality of life has increased in general. But the plateau after the 2000s signals that the easy wins are over. With communicable diseases largely under control, Melanesia’s future health gains will depend on tackling non-communicable diseases, strengthening health financing, and building climate-resilient systems that protect against new shocks.

Figure 4: Distribution of Total Life Expectancies by Decade (All Countries) (1960-2023)

In sum, this post shows three trends in life expectancies. First, the regional catch-up with Fiji; second, the persistent gender gaps in longevity; and third, the overall convergence towards longer, more equal lives across the Pacific’s most diverse subregion. And they all illustrate one of the quiet revolutions in the Melanesian development. Life expectancies went from deep inequality outcomes to near parity in just two generations. One could say, at least, for all countries, overall quality of life has increased compared to that in the 1960s. But equalisation isn’t the same as completion. The region has achieved cross-country convergence. Cross-gender convergence remains an issue.

Data Note

Figures are drawn from World Bank life-expectancy data (1960–2023) for Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. All averages and gender gaps are calculated from the author’s analysis.

Also note that the blog focuses just on the trends and not the drivers of these trends. It would be interesting to explore the drivers but might require a detailed study. This blog is limited by word count.

Ref:

The featured image is sourced from Benar News.

Leave a comment